Exclusively Inclusive.

By Karen Brain

When I think of my experiences with sports, I think about the Arthritis Camp, located at the YMCA’s Camp Marston in San Diego County. I started going to this camp during my early teen years. When it was introduced to me, I remember thinking, “Some stupid camp for kids with arthritis…no thank you.” But if I went to camp, then it would be one week of summer vacation that I wouldn’t be in the hospital for painful physical therapy rehab. Of those two choices, I chose camp every time. I don’t know if it was because I spent so much time in sterile medical settings, or just my personality, but I hated most things about hot weather and outdoor activities. I couldn’t care less about sports, and my idea of acceptable camping was an all-inclusive resort. But there I was, voluntarily going to summer camp. I never imagined how rewarding it would be for me.

Reality started to set in as I reviewed the suggested packing list… “Sunblock? Gross. BUG SPRAY?! What kind of prehistoric land was this?!” Like I said, I’m not the outdoorsy type. I knew my skills learned from hospital roommate experiences and traditional sixth-grade camp would come in handy here – how to change clothes without exposing myself to strangers, and sneaking into the showers at o-dark-thirty to take a “real shower” so I wasn’t dirty and stinky like so many of my peers. I learned no human could adequately clean their entire body in less than five minutes while showering modestly. (Or maybe those without physical disabilities could accomplish it?) I knew I had better pack an alarm clock, flashlights, and batteries for this camp. I didn’t want to shower in the dark…that’s how spiders get you.

Our camp was integrated with another camp of nondisabled kids. It was one of the first times I saw so many kids just like me in one (non-medical) place, AND with nondisabled kids, all with the same expectations. Some of our volunteer counselors were doctors, nurses, physical therapists, and campers’ family members. Some campers needed accommodations to participate in the camp’s activities. The staff communicated with us, were flexible, and willing to work with us to ensure we could participate with our nondisabled peers in ways that were accessible for us. The accommodations were subtle or hidden; it appeared and felt like we were all the same – just kids. This inclusion made the camp experiences just as beautiful as the property.

I was assigned to the Girls’ Large Cabin, which housed the campers with more physical challenges than other campers. This was ideal for me – I had a real bed in a real bedroom with only one roommate, and the bathroom with showers was inside our cabin! While they did assign locations by assumed gender and physical abilities back then, it is important to note that anyone, regardless of gender identity or physical abilities, would be allowed to visit the common areas of any cabin anytime, including bathrooms. For our camp, accessibility and inclusion were priorities over possible social norms suggesting otherwise.

Going to camp, especially in this cabin, taught me how diverse our Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA) population was and made long-lasting friendships. Imagine what it’s like to not see others with disabilities like us in our daily lives, to not see people like us on television or in movies or books, and nobody else in our families is like us either. (I realize some of you reading this know exactly what I’m talking about.) It felt great to be around peers who understand without explanation. Some counselors in this cabin were diagnosed with JRA as children, too. This was extremely meaningful to me; until then, I had never met an adult who had JRA. It made me think that if they could grow up and live “normal lives” with JRA, so could I. Some went to college, some ran their own business, some got married, and some had biological kids (who did not have JRA or any other diagnoses). Some campers and counselors had multiple diagnoses, mostly autoimmune diseases. We traded health-related stories, lessons learned, recommendations, and resources.

My roommate was a rebel teenager who used a power wheelchair and knew all the curse words in existence. Her wheelchair seemed really fast. She taught me how to hop on the back of it, and we’d ride all around the campground. We also stayed up way past lights-out time talking and laughing until we either fell asleep or got in trouble.

Our days started early. Breakfast was at 7:30 a.m. with morning medication distribution. We did activities throughout the day, with lunch and midday medications around noon. Then dinner and evening medications would be around 5:00 p.m., followed by campfire activities, music, and games. We started getting ready for bed and had bedtime medications at 9:00 p.m. But none of us went to sleep at lights-out time like the adults had hoped. Then I’d start the new day at 5:00 a.m. for my solo shower time in the bathroom’s communal shower room.

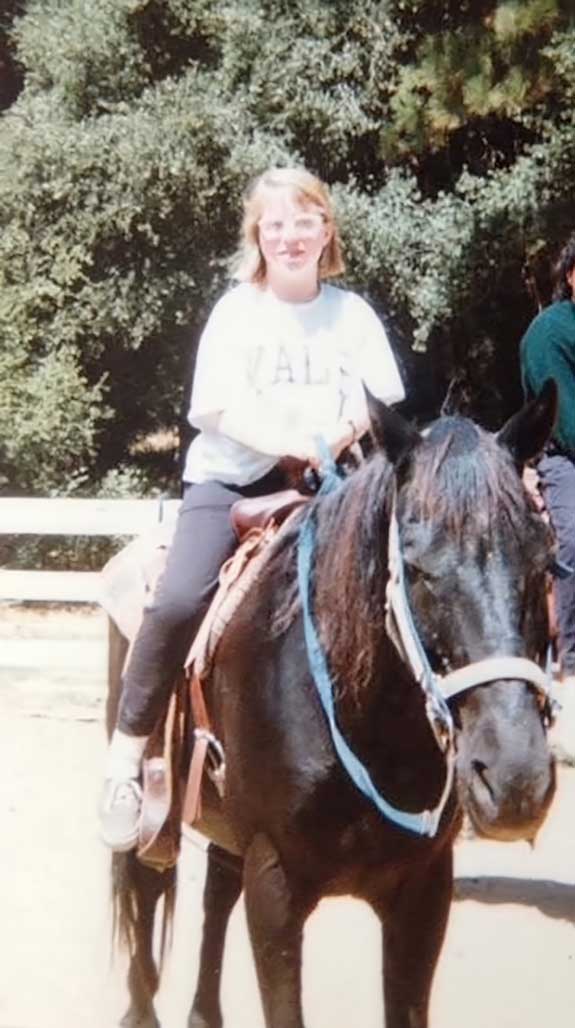

There were many daytime activities at camp. My activities included arts and crafts, swimming, canoeing, archery, and horseback riding. Canoeing was more complicated than I thought it would be, but I improved throughout the week. I couldn’t believe I was able to do archery and horseback riding! I assumed I couldn’t do those two activities. (Maybe because most adults in my world assumed I couldn’t do it either?) I needed accommodations, but I DID IT. With encouragement and assistance from the camp counselors, I did it. I couldn’t wait to tell my family and friends when I got home.

Karen riding a horse at camp.

On the other hand, my roommate argued with the counselors to NOT go horseback riding. The counselors pushed her to do it, saying (assuming) that if she did it, she’d have the same positive response I did. To campers, the counselors pushing her seemed like Abled (or Nondisabled) Saviorism manifested by Ableism, although we didn’t know these terms at that time and age. (It’s like White Saviorism or Cis Saviorism.) Ableism is the social prejudice against and discrimination of people with disabilities based on the belief that nondisabled bodies are superior. Saviorism is the belief in the responsibility to help, fix, or “save” members of a perceived-inferior community, even though such help is unsolicited and often ends up causing more harm than good.

Whether she didn’t want to do it because of fear, anticipated pain, or because it was Tuesday, it was her decision to make. When she said no, it should have been enough; she should have had the right not to go horseback riding. Instead, the arguing continued for too long and became very heated. (By “too long,” I mean about an hour.) For our counselors (who were medical professionals, relatives, and adults with JRA) to deny her agency like that, and to do so while campers watched, it can reinforce ableism and the negative stereotypes of people with disabilities. Did they want her to go horseback riding to satisfy her need, or theirs? It was never her need, nor her want.

Ironically, the counselor who argued the most had JRA like us. With greater awareness of disabled children’s experiences, especially those of the older generations, it’s not surprising that this happened, and it’s not surprising that the counselors with JRA pushed. For older generations, the medical model of disability was prevalent in society. Some might say it’s still prevalent, although outdated. It’s the belief that disabilities need to be cured or “fixed,” focusing on medical treatments and interventions to restore the disabled person’s function to the preferred “normal” abilities. (The social model of disability emerged around the 1980s, and even though it is typically the preferred model within the disability community, it certainly wasn’t widely accepted in society at that time.) When you add Abled Saviorism, it looks like trying to “help” the disabled child do a typically able-bodied activity in efforts to show us “you can be just like the (superior) nondisabled kids.” Furthermore, when the counselors with JRA pushed, it also looked like internalized Ableism and teaching the younger generations internalized Ableism, too.

The aftermath of that argument was rumors, and our counselors blamed my roommate. I don’t remember any of them mentioning the adults’ role in the argument or anything like “maybe she simply didn’t want to go horseback riding.” The difference between my roommate and me was that I really wanted to go, but I feared I’d never be able to because of my disability. Whereas she never wanted to go, but they did everything except strap her to the horse.

For us campers, my roommate became our idol and fearless leader. While uncomfortable to witness, it was a powerful lesson. She taught us we should have a choice and that we can use our voice, especially when it comes to our bodies. She also taught us curse words we’d never heard of before and creative ways to use them. She was fabulous.

One night, a few of us decided to toilet paper the Boys’ large cabin. I had an alarm clock to wake us up in the middle of the night and flashlights to get the job done in the dark. Our communal bathroom stored toilet paper supplies, and my roommate provided our getaway ride. Our work on their cabin was a great piece of art.

They retaliated by stealing ALL of the toilet paper from our communal bathroom. (Luckily, there was some left in our other bathroom!) We retaliated by stealing ALL of their underwear. Long story short, we learned our desire for toilet paper and undergarments outweighed theirs, so we called a truce.

Our cabin did a comedic sketch involving the Energizer Bunny during the talent show. At that time, the Energizer Bunny television commercial showed the too-cool toy bunny in sunglasses and flip-flops interrupting other battery-operated toys, running circles around them to show its long-lasting power and endurance. We dressed my roommate in bunny ears, sunglasses, flip-flops, a toy drum, and a drumstick. The rest of us from the Girls’ Large Cabin performed a parody of the camp counselors’ daily actions around camp, poking fun at the camp rules. When she went across the stage in her power wheelchair as our cabin’s version of the Energizer Bunny banging that drum, it was perfect. It was even better when she went across the stage, interrupting the Boys’ Large Cabin sketch. Of course, we won the talent competition!

My arthritis camp experiences, lessons learned, and friendships made were priceless. If I hadn’t given that “stupid camp for JRA kids” a chance, I would have lost an amazing opportunity with many benefits to come long after camp week ended. When I turned 18, I started volunteering as a camp counselor for the annual JRA camp week. My thought was that I didn’t have role models with JRA in my world when I was growing up until I went to camp, so let me try to be one for the next generations. That was when I learned the full effects of “what goes around comes around.” Campers’ Rebellion was brutal. But that’s a story for another time. Wishing you a wonderful summer and happy Pride Month!

This article was originally published in the 2025 Sports & Recreation Issue of Las Vegas PRIDE Magazine, and can be read in its original format here.